The Kendrick Lamar Test: When and how to use an expository aside

A few examples of expository asides with tips on when and how to use them. My litmus test? The 2025 Super Bowl Halftime Show.

Like scene, summary, insight and reflection, the expository aside is one of the key ingredients of narrative nonfiction. It’s particularly important in narrative journalism, when a story serves as a vehicle to explain something complex to the reader.

What is an expository aside? It’s a brief diversion from the narrative, when you “break scene” and go into explainer-mode to tell the reader something important. It’s like pressing “pause” while watching a Netflix show with your mother, so you can brief her on the pop culture memes that will otherwise sail over her head.

My favorite real-life example hit me during the 2025 Super Bowl Halftime Show. I was watching it with my teenage son, who brought me up to speed on the 2024 Diss Track feud between Kendrick Lamar and Drake.

If you didn’t know this Diss Track history—what a NYT critic called “an incredibly hot, burning, deeply toxic exchange of songs”—you would miss the layers of meaning sprinkled through the lyrics, the show, and even the wardrobe.

Case in point: The next day, Facebook was filled with dismissive comments and ignorant criticism of the half-time show by people who Just. Didn’t. Get it.

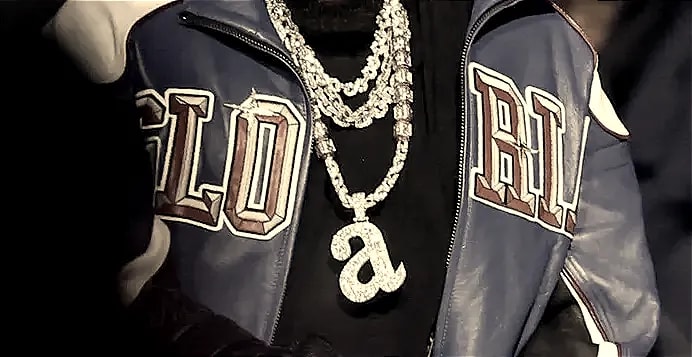

If you knew the backstory (even if, like me, you’re not a huge consumer of rap) you got the lyrics, the symbolism, and the show. Maybe you even noticed the blinged-out lowercase letter “a” dangling around Kendrick Lamar’s neck and recognized it as an allusion to a lyric from “Not Like Us.”

This line is the most devastatingly clever “diss” in the whole Diss Track war, the atomic insult you can hear echo through the Super Bowl stadium as everyone in the know sang along:

Tryna strike a chord and it’s probably A MINOR!

That’s a Shakespearean-level insult, by the way. A triple entendre. IYKYK. (And if you don’t know, watch this.)

I noticed another great example of an expository aside in “The Man Who Broke Physics,” Sally Jenkins’s story in The Atlantic about Ilia Malinin, a 21-year-old figure skater headed to the Olympics.

This aside expands the audience of the piece beyond figure skating fans. Even if you don’t know a triple-lutz from a salchow, you can grasp—and be awed by—the athleticism illustrated by the following expository aside:

To fully appreciate how revolutionary Malinin is, consider some fundamental physics and biomechanics. The gold-medal-determining long program, also known as the “free skate,” lasts for four and a half minutes. Roughly 30 seconds in, Malinin’s heart rate rises to 90 percent of its capacity, about 180 beats a minute, and stays there for the duration. The effort is comparable to that sustained by the world’s fastest milers.

Wearing carbon-composite skates that weigh about two pounds each, Malinin reaches a vertical leap of approximately 30 inches on his quad axel—one kinematic study captured it at 33 inches, similar to the standing vertical leaps of NBA players such as Stephen Curry, Devin Booker, and Kevin Durant. He lands on a blade that is just 3/16 of an inch wide.

Malinin enters the jump skating at about 15 miles an hour. As he snaps into his shoulder turn, he draws his arms and legs inward, creating a spin. At this stage, he experiences at least 180 pounds of centripetal force. By way of comparison, a NASCAR driver rounding a corner will experience about 400 pounds of centripetal force, while wearing a seat belt. As he reaches his apex, Malinin is spinning at 350 revolutions per minute. This is about the same as a kitchen stand mixer or the marine engine of an oil tanker.

Expository asides are not just an element of nonfiction. Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist Anthony Doerr weaves historical and technical asides into his fiction. In All the Light We Cannot See, it appears in dollops about atoms, radio waves, or the electromagnetic spectrum. In The Shell Collector, it informs scenes of a scientist handling a tiny mollusk with a lethally poisonous bite:

Under a microscope, the shell collector had been told, the teeth of certain cones look long and sharp, like tiny translucent bayonets, the razor-edged tusks of a miniature ice devil. The proboscis slips out the siphonal canal, unrolling, the barbed teeth spring forward. In victims the bite causes a spreading insistence, a rising tide of paralysis. First your palm goes horribly cold, then your forearm, then your shoulder. The chill spreads to your chse. You can’t swallow, you can’t see. You burn. You freeze to death.

One of my favorite literary examples is one I spotted in H is for Hawk, Helen Macdonald’s memoir about training a goshawk as she grieves the sudden death of her father. I’ve included a 500-word passage so you can see how seamlessly it tucks into the narrative, between a flashback scene and the author’s personal reflection on the scene and what it means.

The expository aside (bolded below) sets up the insight in the author’s reflection, elevating the meaning into something more expansive. This is an example of how the best first-person writing is “not just about me.”

In a scrapbook of my childhood drawings is a small pencil sketch of a kestrel sitting on a glove. The glove’s just an outline, and not a good one—I was six when I drew it. The hawk has a dark eye, a long tail, and a tinny fluffy spray of feathers under its hooked beak. It is a happy kestrel, though a ghostly one; like the glove, it is strangely transparent. But one part of hit has been carefully worked: its legs and taloned toes, which are larger than they ought to be, float above the glove because I had no idea how to draw toes that gripped. All the scales and talons on the toes are delineated with enormous care, and so are the jesses around the falcon’s legs. A wide black line that is the leash extends from them to a big black dot on the glove, a dot I’ve gone over again and again with the pencil until the paper is shined and depressed. It is an anchor point. Here, says the picture, is a kestrel on my hand. It is not going away. It cannot leave.

It’s a sad picture. It reminds me of a paper by the psychologist D. W. Winnicott, the one about a child obsessed with string; a boy who tied together chairs and tables, tied cushions to the fireplace, even, worryingly, tied string around his sister’s neck. Winnicott saw this behavior as a way of dealing with fears of abandonment by the boy’s mother, who’d suffered bouts of depression. For the boy, the string was a kind of wordless communication, a symbolic means of joining. It was a denial of separation. Holding tight. Perhaps those jesses might have been unspoken attempts to hold on to something that had already flown away. I spent the first few weeks of my life in an incubator, full of tubes, under electric light, skin patched and raw, eyes clenched shut. I was the lucky one. I was tiny, but I survived. I had a twin brother. He didn’t. He died soon after he was born. I know almost nothing about what happened, only this: it was a tragedy that wasn’t ever to be spoken of. It was a time when that’s what hospitals told grieving parents to do. Move on. Forget about it. Look, you have a child! Get on with your lives. When I found out about my twin many years later, the news was surprising. But not so surprising. I’d always felt a part of me was missing; an old, simple absence. Could my obsession with birds, with falconry in particular, have been born of that first loss? Was that ghostly kestrel a grasped-at apprehension of my twin, its carefully drawn jesses a way of holding tight to something I didn’t know I’d lost, but knew had gone? I suppose it was possible.

—From Chapter 5: Holding Tight (p 48 in the hardcover)

It’s worth noting that a well-deployed expository aside is like salt in a recipe. It enhances the other ingredients.

When should you use one? When the reader needs to know something important to understand the next scene. Without it, the full meaning of the scene would be lost. (See: My Kendrick Lamar test.)

Like salt, expository asides should be used deliberately and sparingly. A little goes a long way. Too much can ruin the whole story (or dish). Why? Pacing. Expository asides used in excess can stall the narrative momentum.

When I think about narrative pacing, I imagine Scene as a “Play” button on a movie that’s running inside your reader’s head as they read your story. Summary is like a “Fast Forward” button, condensing time and getting the reader quickly to the next scene. Expository Asides are like a “Pause” button.

Just don’t press pause for too long. Your reader is anxious to get back to the Halftime Show.

These are such great examples. Thank you!

Kim, thanks for this. Great examples and fantastic explanation.